CHAPTER SIX - On to Italy

Our first group of replacement pilots were welcomed with vigor. To us old 23-year old "old timers" most of them seemed pretty young -- 20 and 21 going on 22. They were good pilots, their attitude was outstanding and the pre-combat training period gave us plenty of flying but a well deserved rest from combat. We also had the privilege of providing pre-combat training to some extra pilots who were shipped out to other outfits. They were all great guys and we hated to see them go.

You may have wondered what happened to "Hell's Belles Off Duty" -- that painting of a gorgeous nude Belle lounging in a glass of champagne. You will remember that the artist, whoever he was, created this masterpiece on a mattress cover. She was only unveiled as a morale booster on special occasions in the Squadron, but I never knew who took care of the painting between times. I "inherited" it by accident.

|

|

Hells Belles, but not the painting of the gorgeous nude Belle lounging in a glass of champagne. |

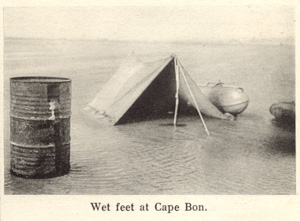

On the dreary morning after our cloudburst, when the Cape Bon lake bed airport and camp was unexpectedly flooded, we were hastily evacuated to a nearby temporary base. Just before our jeep pulled out I strolled past the area where our Officers' Mess Club tent had been, noticing that more than the usual amount of things had been abandoned (understandable under the circumstances). Among the items was a chest of drawers, which seemed in fairly good condition. Out of curiosity I opened the drawers. Nothing was inside any of them except the bottom drawer. There neatly folded but soaking wet was "Hell's Belles Off Duty." I put the painting in my B-4 bag as we hurried to load up and catch up with the convoy.

|

|

In a few days when the sun came out I unfolded the painting, to finish drying it. Although the desert dust in the mattress cover showed watermarks, the painting itself survived in great shape. No one ever questioned my right to keep it. When new pilots completed their pre-combat training, their initiation was considered incomplete until they had heard the Squadron traditions speech and reflected proper respect and appreciation for our insignia; on and off duty versions. Asked to display "Hell's Belles Off Duty" at reunions, I have been gratified that the reactions of wives have been of art appreciation and not shock.

It is true we were an eager outfit when we took the big leap over to Cercola, Italy, at the northern base of Mt. Vesuvius. Naples had been taken only a few days before our arrival. As the sound of artillery could still be heard to the North, we felt very much a part of the war zone again. It was the beginning of a long year of intensive combat with few breaks.

My Amalfi/Capri break was not preplanned. On my seventh mission out of Cercola (12 Nov. 1943) we had a dive bombing target on a little town (rail and road junction) inland and in a valley between pretty steep and high mountains. Being very cagey we flew as if to pass the area, then shifted to echelon quickly and peeled off left in a direction so that pull out would be back towards our lines. I felt that we had surprised them because there was no sign of light or heavy flak. As I topped out after pull out from the bomb run, and started a slow turn to the left so the rest of the eight ships could join up, the end of the world came!

The 88 exploded, I swear, in the notch between my left bank of exhaust stacks and a point just above the left wing and in front of the 50 Cal. gun barrels. The reason I'm so sure of the exact location is that I saw the black smoke blossom start just as I heard the loudest noise since the creation of the world. There was so much black smoke in the cockpit, I couldn't see or breathe for awhile. My automatic reaction was a full throttle, full aileron, rolling dive to the right; then a zag left to a heading for the bomb line, leveling off just to keep the airspeed needle under the red line. Murph Fenex said, "Hey, J.T. you're making it hard on the troops." I looked back and the flight was strung out trying to catch me, but never would have made it. I cussed the 88's on the radio and did a climbing left arc so the flight could join up and said, "If you're going home with me you'd better hurry." Someone who had seen the flak burst asked, "Bad?" I said, "I don't know, but my leg is bleeding a little." But what bothered me most was my eyes.

I didn't know if it was blood, tears, or just sweat, but my face was wet. When I wiped my cheek with my hand it didn't help because my hands were cut and bloody also. I could see that glass covers over several instruments were shattered, so I figured there must be glass in my eyes. I wondered if I could fly home without blinking -- had to try because I could feel the scratching every time I blinked and didn't know how bad it was.

There was round two-inch hole at the base of my left-hand glass windshield panel (which was partially shattered) but the engine ran as smooth as V-12 music can. I knew by that time that my leg was OK because it began to hurt -- the only pain I ever appreciated, as the feeling came back.

As Cercola came into sight, I began to feel much better; I didn't exactly feel like trying to draw streamers on peel off. As I rolled out on the turn from downwind to base leg, I reached for the gear-down switch with my index finger and couldn't find it. The gear-down switch on a P-40 is a rig looking somewhat like a praying mantis on the front of the stick just below the gun trigger. I looked down and all I could find was the nub of the lever protruding about 1/4 inch. It worked when I pushed up on it; the gear came down and locked OK and it seemed like the Good Lord had remembered me again.

Doc Dorger met me at the revetment. When he climbed up on the wing I handed him two small pieces of the Aluminum gear down lever, which had lodged in my knee. The worst a/c damage seemed to be from the piece of shrapnel which had entered at the base of the left windshield panel, angled downward knocking off the gear switch lever, skinned my shin (it could have just as easily taken my leg off), and exited the cockpit on the lower right side.

Doc scrubbed and painted my shin, stiched my knee (the cut was not too bad) and sent me to a hospital in Naples to have my eyes swabbed, as he put it. That was the worst part; those eye doctors, after flushing the eyes a few times, tweezered out a few glass slithers and then literally swabbed my eye balls about as gently as they would a ship's deck, cracking jokes all the time like knotheads.

When I got back to camp, McCormick and Brandt brought me a piece of 88 shrapnel about 3/8" x 3/8" x 1 1/2" long. When it exited the cockpit it then had penetrated the right wing and they had found it lodged in the wheel well. I still have that piece of shrapnel and the aluminum pieces in my souvenir cigar box. So that is how I happened to be shipped off to rest camp the next morning.

The rest camp had just recently been opened at Amalfi on the Sorrento peninsula. It was a small hotel perched on a cliff over the water. The scenery was great, but it was the food that made it all worthwhile. The indigenous staff had been retained and they seemed to have plenty of fresh vegetables and meats to work with. They could even make a super western omelet using powdered eggs -- unbelievable.

Rest camp was a welcome respite, but could in no way be called restful. On the second or third morning at breakfast it was announced that we would move to a hotel on the Isle of Capri, departing at mid-morning. The hotel staff panicked as if they had not expected to move. Never was a move so boloxed up -- the German U-boat rumors didn't help. We were finally trucked down to a little port on the south side of the peninsula. Our party consisted of about 15 "rest campers" and about that many hotel staffers. Boat departure time came and went as several trips had to be made back up the hill to pick up stuff that had been forgotten -- and finally another trip to retrieve the lunch sandwiches.

Our departure was so late and the little rickety tug so slow (we guessed four knots at full speed) that the all-daylight trip turned to a night-time nightmare. We barely made the west end of the peninsula by nightfall, and then had to navigate the passage between the peninsula and Capri, then a dogleg course in the bay of Naples to the port on the northern coast of Capri. The weather was chilly and not too bad, but the bay was choppy enough that our decrepit boat could barely maintain direction much less headway. About 10:00 PM we made port, but by that time we pilots had made a plan to prevent one segment of pandemonium.

For the trip some unthoughtful character had secured all our booze in the hold except for a little beer, which had long since been dispensed. So we appointed a committee to make sure that the booze was the first category of goods to be transported to our new hotel. The next revolting development was the discovery that we were expected to carry our own bags. We would have revolted if we had known how many sets of steep steps and cobble stone trails there were or how high we had to climb to the Hotel Morgano.

The Morgano had apparently been closed for a short time since the Germans pulled out and we were expected to reactivate it. So we dragged our B-4 bags across the threshold and left them in the middle of the lobby and went straight to the bar. To describe our mood I will only say that if the first case of booze had not arrived at that moment the Hotel Morgano would have been taken apart, brick by brick and stone by stone -- its destruction would have been worse than that of Pompeii.

One of the pilots with talent printed a sign that read, "This bar will be closed for cleaning purposes every morning between 7:45 and 8:00 AM. Someone noticed blood on the floor and we discovered that the stitches in my knee had popped out. It was decided that a handkerchief bondage would suffice until morning. One of my friends said, "J.T., you can stay but you've to stop bleeding all over the gawdamned floor!" No one went to bed that night because we vowed to make sure our bar regulation was followed.

Interest in donkey rides around the island didn't last long. At a time like that one can stand only so much beautiful scenery. The Blue Grotto was very interesting, like one of the wonders of the world to me; although while on the inside I wasn't too comfortable knowing we had to wait for a trough between waves in order to get out. The boatman had sung loudly all the way from the harbor to the cave entrance. On the way back his third or forth rendition of come back to "Come Back to Sorrento" was tolerated, but when he started another ear drum splitting version of "0 Solo Mio" we couldn't stand it anymore -- we had to threaten to throw him overboard to get him to shut up.

It has been said human nature in wartime doesn't really change it, but it certainly reverts back to the basics. The people of the port area of the Isle of Capri were like those of any other small Italian wartime village -- not starving but poorly dressed and willing to beg, borrow, or steal as a way of life; no surprise. The numerous fancy villas on the island seemed to be closed up, with no sign of life. There was life as we discovered later.

Base Command (the outfit that operated the Military Government of the area, the Port of Naples, PX, other logistics activities, and our rest hotels) decided, since we were the first Americans to colonize the island since the Germans and Italian military pulled out, that there should be a Sunday afternoon tea party. A big crowd descended on Morgano as if the invitations to the inhabitants of the villas were summons. The first disappointment was that nearly all of them were a generation or two older than we were and ugly as sin. They were all overweight, expensively dressed, and were from several countries of Europe as well as from Italy. None admitted to being able to speak English, but they had no trouble understanding it. They acted frightened as if they expected us to do them bodily harm. All the stories were similar; their husbands had abandoned them in this hopefully safe place, or had been taken away or killed by the Germans.

The hotel staff probably knowing what to expect, prepared the greatest variety and quantity of finger sandwiches, hors d'oeuvers, and cookies I've ever seen before or since. When all this was placed on tables these elegant "countesses" reverted from restrained and fearful to wild-eyed neo-hysterics -- any fear left was that they might not get their share. It became readily clear why all the guests had brought large purses. They would pick up two or three items, eat one and drop the others slyly into their handbags. I could have done without this insight into human nature. I noticed one oversized old "countess" wearing a fancy white lace dress, hat and gloves to match, had an enormous handbag. She had given up all pretenses of reserve, started holding the open bag at table level and raking everything in arm's reach into it. She saw me observing, turned white and froze as if she expected me to chop her hands off. As I walked out in disgust her mouth was bobbing open and shut but no sound was emerging.

In war zones with few exceptions fear seemed to be all-pervasive. The speed of emotional swings is amazing. The sound of a siren brings instant breath-stopping terror. The whole town of Naples could be out of sight in less than 10 seconds. With the all clear signal given the street activity would be back to normal before the blanch had disappeared from the faces of the people.

[Previous Chapter] [Table of Contents] [Next Chapter]