CHAPTER NINE - Bombing the Hitler Line

There was one time when I was not careful enough with my dead reckoning, and Mt. Vesuvius and broken clouds conspired to do us in. Corky Coward almost lost his life. After our bombing run we had a last light cover mission for the beachhead. Coming home at dusk was usually no problem because Vesuvius' fire and smoke gave us a beacon. We were accustomed to twilight landings without runway lights. This night an overcast obscured the volcano and darkness came earlier, but we were following the coastline. We had to stay west of Gaeta to avoid flak and then take a heading for Naples. As scattered clouds began to form below our altitude a little worry began to creep in. Somebody said, "Hey, J.T., they're trying to raise you." Turning up my radio volume all the way, I said, "Thanks, relay." I barely heard the controllers' message, but the guy with the good ears relayed, "Take a heading of __ degrees and descend." I did and let down to about 1500 feet through scattered clouds to find we were over the bay of Naples. I had everybody string out in trail and took a heading for Cercola which brought us close enough to see the field and the vehicles with lights on (set up along the runway by the people on the ground sweating us out). We dragged the field at a slight angle and began a wide circle to space ourselves for landing, each man having to stay close enough so as not to lose sight of the man ahead of him.

Somebody said, "Corky has problems," but I didn't know he had crashed until everybody else was on the ground. His wingman said his engine had quit. We debriefed quickly while the men in Ops were calling all around to locate Coward. We finally found the designation and general location of a field hospital there they had taken him. Finally, about midnight we found him -- on a stretcher at a field hospital that was a pretty busy place. I asked him if he was hurting. He answered, "No, but it doesn't feel very good either." I could see that he had those infamous gunsight marks on both his forehead and chin. A bad cut on his nose and cheek scared me too. I told him not to try to talk anymore and that we would find the doctors.

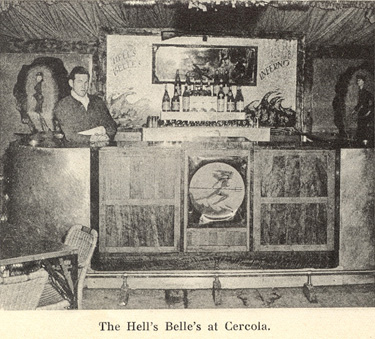

Fortunately, they had given Corky first aid and morphine for pain as soon as he was brought in, and were just about to take him into surgery. After surgery the Doc told us that he had a concussion and pretty bad cuts, but would survive OK. It was almost sun-up. We didn't talk much on the way to Cercola.

Piecing everything together, it seemed that knowing he would not make Cercola with the engine cutting out, and being too low to bail out Corky wisely chose to land in a large lighted open area belonging to a truck transport battalion. On the approach he struck some electric lines and some trees and cartwheeled into the truck assembly lot. The troops had rushed right out to find that the only piece of the P-40 left intact was the cockpit with Corky still strapped inside, unconscious. That he had lived through all that was without doubt a miracle.

Around the bar, we used to sing, "10,000 dollars going to the folks," and laugh. After the losses and near losses we had experienced, the song didn't seem very funny anymore.

|

|

This period of the war -- support for our troops on the Hitler Line and the Anzio support prior to the breakout -- was the toughest period of the war for the 316th Squadron from the standpoint of duration and intensity of these operations and intensity of enemy flak. Air opposition remained spasmodic, but frequent enough to keep us on our toes. It is hard to say which of our mission categories, close support or interdiction, was more important, but we considered ourselves more effective than any other outfit at both.

Flying two or three of those missions a day nearly every day tended to make us lean and mean. One day we had bombed our enemy artillery battery target and were doing our patrol time over the beachhead. I must have been thinking about our poor bastards down there in their holes when I decided to do something that might shake up the Jerries a little bit. I was certainly not thinking about all the times we had talked about not doing stupid things unless we had to.

One section of the bomb line at that time was a stretch of railroad track -- anything on the easterly side of that track was enemy. As we turned for our last patrol lap from south to north I told top flight to maintain cover while we did a little strafing run. Leaving about 9000 feet we rolled out of the turn line abreast in a steep dive parallel to the bomb line on the enemy's side. Coming down like bats out of hell, we spread out a little wider at about 3000 feet and started firing as we came right on down to the deck. We hosed them like demons for three or four miles.

I had not realized that there could be so many Germans in the ditches and wadis that close to the bomb line. I could see them and signs of them everywhere; and it seemed like every damned one of them were shooting back-at us. I was absolutely sure of that when a German helmet, passed right over the top of my right wing -- there wasn't a head in it so somebody had been mad enough to throw it at me. I decided maybe that was enough and called a left turn to climb back to altitude over our territory. There was no real way to assess what we had done to the enemy, but we brought back enough holes in the birds to prove that we knew where they were and that they were there in force.

[Previous Chapter] [Table of Contents] [Next Chapter]